Portal to the Deep

The deep sea covers over 60% of our planet, yet less than 1% of it has been explored. [1] Dive in to learn more about Guam’s unique deep-sea ecosystems.

The Sunlit Zone

The sunlit zone is the sunny, shallow, top layer of the ocean where most marine species live. This zone reaches down to 656 ft deep, which is the deepest point where photosynthesis can still occur.

0-656 ft deep (0 - 200 m) [2]

Lots of sunlight, warm water, and abundant food

A Pacific double-saddle butterflyfish (Chaetodon ulietensis) on the reef in Piti.

-

The sunlit zone is home to plants, algae, phytoplankton (plant-like plankton), and most corals since these species rely on light for photosynthesis.

The abundance of phytoplankton in the sunlit zone is particularly important because not only do they produce oxygen as a result of photosynthesis, but they also support the entire food web. [3]

Here’s how: phytoplankton are an important food source for zooplankton, which are tiny, free-floating animal plankton. Zooplankton, like krill and small shrimp, feed larger organisms like plankton-eating fish, filter-feeding clams, and even large animals like blue whales.

Since there are so many species living in the sunlit zone, each creature must find its own unique way to adapt and survive.

Some blend in using countershading: being dark on top to blend in with the dark ocean below, and a light underside to blend in with the sunlit ocean. This way, they go undetected by predators and prey looking at them from above and from below.

Pelagic, or open ocean, creatures like sharks and dolphins typically use countershading.

Some are bright, vivid colors or patterns to signal to predators that they are poisonous or venomous.

Some try to blend in with their surroundings, whether that be the tan-colored sand, colorful coral, brown rocky substrate, or other shallow habitats.

The Twilight Zone

The twilight zone is the dimly lit midwater zone of the ocean and is considered to be where the deep sea begins. The bottom of the twilight zone is the deepest point that light can penetrate.

656-3,300 ft deep (200-1,000 m) [2]

Dim sunlight, near-freezing water, and scarce food

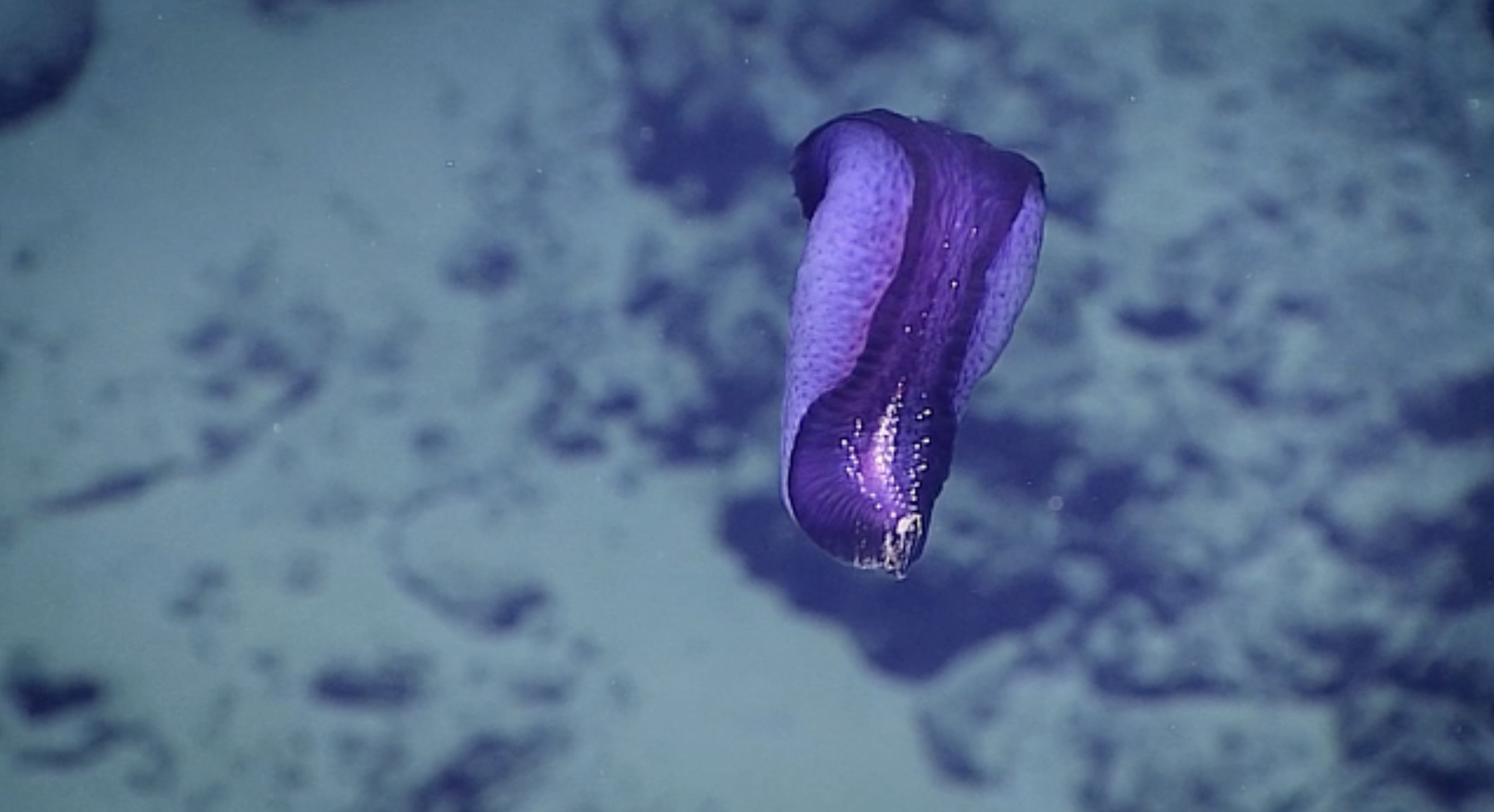

A deep-sea swimming balate’! Photo: 2016 NOAA Mariana Trench expedition.

-

Once you get into the twilight zone, the water is on average 39 degrees F (4 degrees C), which is only a few degrees warmer than freezing! [4] On top of that, the light is very dim and the pressure from the mass of water above is increasingly strong.

Few creatures can tolerate these harsh conditions, but the ones that can have very unique adaptations that allow them to survive. For example:

Some have huge eyes for seeing in dim light!

Since the twilight zone is mostly the open ocean with no seafloor to rest on, many species are gelatinous and lightweight and drift through the open seas, like jellies and siphonophores.

Most creatures in the twilight zone use bioluminescence: the ability some species have to produce light through a chemical process in their body. Bioluminescence is used in many different ways:

To attract and catch prey, like the anglerfish, which dangles its bioluminescent lure right in front of its mouth to attract curious prey and snap them up if they get too close

To attract mates.

To see their surroundings.

To scare off predators, like the firefly squid, which squirts out bioluminescent ink to stun and ward off predators.

To blend in! This is called counter-illumination: some species have bioluminescent spots on their underside, and when they glow, they blend in with the dimly sunlit surface. But for a predator looking down on them from above, their dark topside blends in with the darkness below.

The Midnight Zone

The midnight zone is the ocean’s pitch black depths, too deep for sunlight to reach. This zone accounts for 70% of the ocean, making it the largest habitat on Earth. [5]

3,300-13,100 ft deep (1,000-4,000 m) [2]

Zero sunlight, near-freezing water, and scarce food

A pricklefish (Malacosarcus sp) seen on the 2016 NOAA Mariana Trench expedition.

-

With no sunlight, many creatures barely use their sense of sight and have heightened senses of smell, touch, taste, and hearing to get around. Some even have adapted unusual appendages to help them better sense their environment.

For example, the tripod fish has long tripod-like fins, which act as stilts and also act as sensitive antennae that can detect movement in the water.

Meals are few and far between, so many midnight zone species have extendable stomachs and huge mouths so that whenever food does drift down, they can eat the entire thing right then and there.

For example, the gulper eel can expand its jaw to engulf massive prey if needed.

Due to limited supply of nutrients, many animals rely on filter-feeding from currents, or eat tiny bits of decaying organic debris that slowly sinks from the surface waters known as “marine snow”. Other animals take advantage of “whale falls”: a rare occurrence in which a dead whale sinks all the way to the bottom of the ocean and becomes a meal for many deep-sea scavengers.

The Abyssal Zone

13,100-19,700 ft (4,000-6,000 m) [6]

The abyssal zone makes up the deeper depths beyond the midnight zone. Three-fourths of the ocean’s seafloor exists at these depths [6]

The Hadal Zone

19,700-36,070 ft (6,000-10,994 m) [6]

This zone only occurs in deep-sea trenches, and only a few parts of the world are home to trenches this deep. [7] Deep-sea trenches occur where two tectonic plates meet and one plate slides under the other.

The Mariana Trench

The deepest part of the ocean happens to be right in Guam’s backyard: the Mariana Trench.

At its deepest point, the Challenger Deep, the Mariana Trench reaches 35,876 ft (8.8 miles) below sea level. [8]

-

This trench was created when the Pacific tectonic plate was pushed under the Philippine tectonic plate.

The trench is 50,532,102 acres, which is five times longer than the Grand Canyon. [9]

The Mariana Trench is deeper than Mount Everest is tall! [9]

The Challenger Deep was named after the HMS Challenger, which was the first oceanographic survey ship to chart its depth in 1875 [8]

Where is the Mariana Trench?

The Mariana Trench is a long, crescent-shaped trench that hugs the Mariana Archipelago, including Guam and the CNMI. On average, it is approximately 124 miles east of the Mariana Islands. [10]

Most of the Mariana Trench lies within the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and Guam, and a small part of the trench, including the Challenger Deep, lies within the EEZ of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). [11]

Map of the U.S EEZ surrounding the Mariana Trench. Credit: Hourigan et al. 2021

Who manages the Mariana Trench?

For the part of the trench in Guam’s and CNMI’s waters, the Mariana Trench National Marine Monument was established through presidential proclamation in 2009 to protect the trench’s geographical features and unique deep-sea ecosystems. [12]

-

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA jointly manage the Mariana Trench National Monument, in collaboration with the CNMI government, the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Coast Guard, and the Mariana Trench Monument Advisory Council. [9]

The Mariana Trench National Marine Monument spans 95,216 mi^2 and includes 3 main areas, or “Units”: the Island Unit, Trench Unit, and Volcanic Unit. The Trench Unit has been designated as the Mariana Trench National Wildlife Refuge, and the Volcanic Unit has been designated as the Mariana Arc of Fire National Wildlife Refuge. [12]

This Monument also includes the Sirena Deep, which is the second deepest point in the Mariana Trench, and the third deepest point in the entire ocean. [12]

Mariana Trench National Monument website: https://www.fws.gov/national-monument/mariana-trench-marine

Mariana Trench National Monument Poster created by NOAA fisheries. Access the full poster here

How has Guam been involved with the Mariana Trench?

-

This trench was originally named “the HMRG Deep” after the group that discovered it in 1997, but was renamed “the Sirena Deep” after a local contest was held in 2009 for local Guam and CNMI students to submit their ideas for a new name. [13]

-

She participated in a 2009 expedition with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute and a 2014 expedition with the Schmidt Ocean Institute. She has also participated in other deep-sea expeditions in other areas.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute 2009 Mariana Trench expedition: https://archives.whoi.edu/nereus/main/nereus/mariana-trench-2009.html

Schmidt Ocean Institute 2014 Mariana Trench expedition: https://schmidtocean.org/cruise/exploring-the-mariana-trench/

-

While the trip was unfortunately cut short due to poor weather, [16] the team still managed to make a significant discovery. At 6.6 miles deep, these scientists recorded the deepest sighting of xenophyophores, which are some of the largest single-celled organisms on the planet. These xenophyophores are only found in deep-sea ecosystems, but previously had only been found 4.7 miles deep. [15]

-

Learn more about the Aquarium of Guam, formerly known as Underwater World: https://www.aquariumofguam.com/

-

The display includes a sample of deep-sea mud and volcanic rock extracted from the Mariana Trench on a recent expedition.

Learn more about the Guam National Wildlife Refuge: https://www.fws.gov/refuge/guam

-

The winning names were: Paraliparis echongpachot, since echong pachot means “crooked mouth” in CHamoru, and the fish has a characteristically crooked mouth; and Paraliparis kadadakaleguak, since kadada’ kaleguak means short rib bones, which is a feature of this species. These new scientific names were officially published and accepted in 2021. [17]

-

Aboard cruise NA171 in May 2025, exploring the Mariana volcanic arc:

Shannon Seleen, GDOE GATE teacher, served as a Science Communication Fellow.

Amanda Dedicatoria, freelance science communicator, served as the Lead Science Communication Fellow

Amanda was also a Science Communication Fellow aboard the E/V Nautilus’ expedition in Palau in 2024 and presented at the Guam museum in 2025 about this expedition and our connections to the deep sea.

Aboard cruise NA172 in June 2025, exploring mud volcanoes and the Mariana Trench:

Amber Pineda, UOG undergraduate, served as a ROV Engineering Intern

Shelterihna Alokoa, community educator, served as a Science Communication Fellow.

Linda Tatreau (front row, blue shirt) with the Schmidt Ocean Institute research team on their 2014 Mariana Trench expedition. Photo: Schmidt Ocean Institute

The preserved specimen of the deep-sea snailfish named by Guam students: Paraliparis kadadakaleguak. Photo: Brian Sidlauskas, Oregon State University

Deep-Sea Exploration History in the Marianas

-

1960 - the first expedition to the Challenger Deep with Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh aboard the bathyscaphe, Trieste

2012 - the second expedition to the Challenger Deep with James Cameron aboard the DEEPSEA CHALLENGER submersible

2019 - the third expedition to the Challenger Deep with Victor Vescovo aboard the deep submergence vehicle (DSV) Limiting Factor

2021 - first pacific islander to descend to the Challenger Deep, Micronesian Nicole Yamase, along with Victor Vescovo aboard the DSV Limiting Factor

2022 - recent expedition to the Challenger Deep with Dawn Wright and Victor Vescovo aboard the DSSV Limiting Factor

-

2009 Mariana Trench expedition with Guam teacher Linda Tatreau on board: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution - R/V Kilo Moana and hybrid remotely operated vehicle (HROV) Nereus

2014 Mariana Trench expedition with Guam teacher Linda Tatreau on board: Schmidt Ocean Institute - R/V Falkor

2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Mariana Islands: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research - NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer

2025 Mariana Arc Volcanic Exploration (NA171): The Nautilus Live, Ocean Exploration Trust - E/V Nautilus

The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Deep Discoverer being recovered after a dive on the 2016 NOAA Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas.

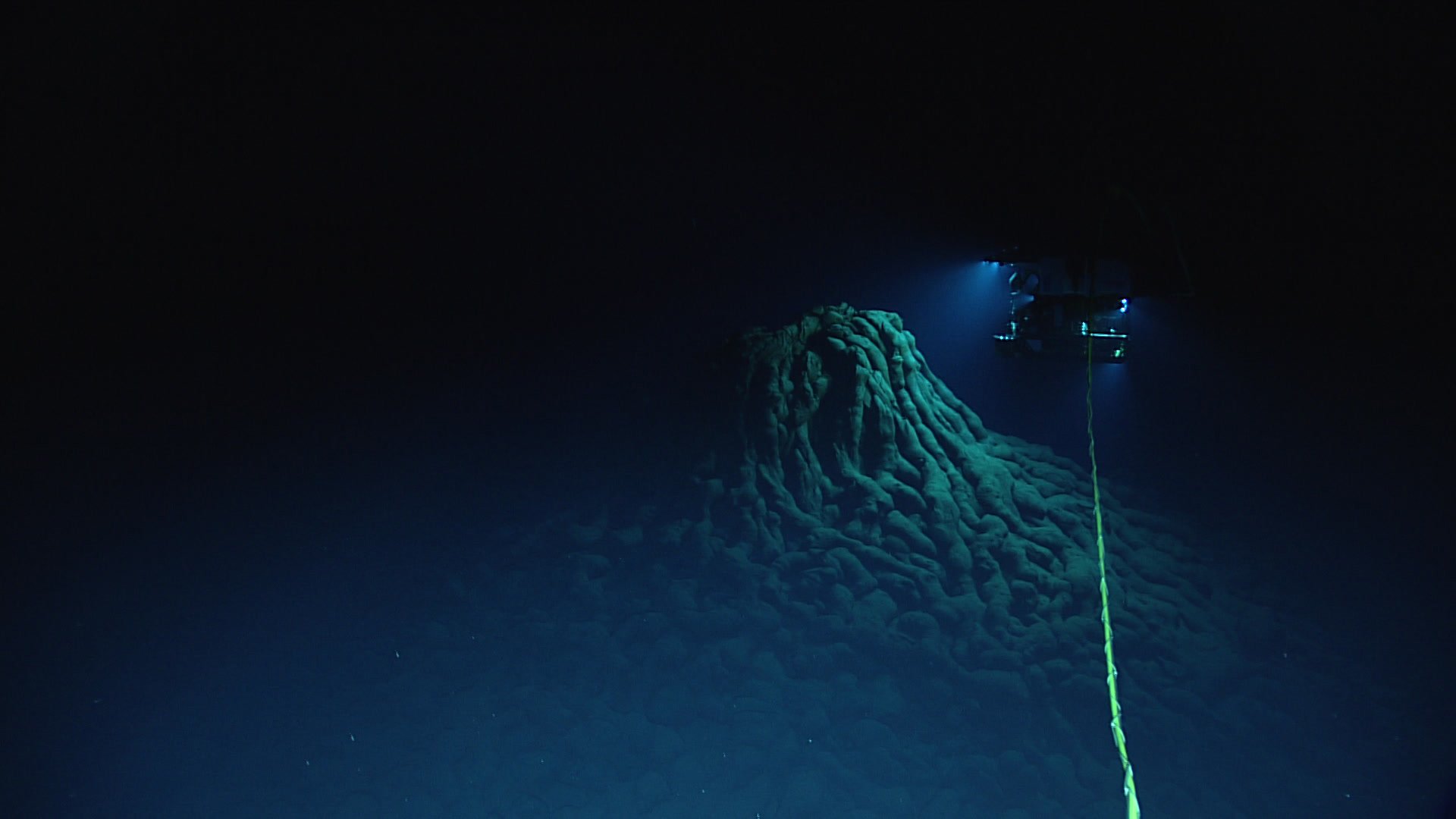

Hydrothermal Vents

The Mariana Trench is lined with deep-sea volcanoes and other geological wonders like hydrothermal vents, mud volcanoes, and pools of molten sulfur! [18]

For example, the Eifuku submarine volcano looks like a series of underwater chimneys spewing extremely hot carbon dioxide measured at 217 degrees Fahrenheit. [18] This particular underwater chimney pictured in the background is called “Champagne vent”. Photo: Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NOAA/PMEL, NSF

Check out the incredible hydrothermal vents of the Hafa Adai vent field from the E/V Nautilus’ 2025 Mattingan: Mariana Arc Volcanic Exploration (NA171) expedition. Video by the Ocean Exploration Trust/ Nautilus Live, NOAA

Mussels and shrimp surrounding a vent in the Mariana Trench. Photo: Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 - Ironman, NOAA/PMEL, NSF

Tube worms living by the hydrothermal vents of Toto Caldera in the Mariana Arc of Fire. Photo: Ocean Exploration Trust/ Nautilus Live, NOAA

-

Some animals live by hydrothermal vents, which are like underwater volcanoes that release heat and minerals into the water.

Some bacteria in these hydrothermal vents can even do chemosynthesis, which is similar to photosynthesis but uses chemicals from these hydrothermal vents instead of sunlight to produce food.

Much like phytoplankton form the base of the food web in many shallow-water ecosystems, these chemosynthetic bacteria form the base of the food web in many hydrothermal vent ecosystems. These bacteria are preyed on by small shrimp called amphipods and copepods, which are then preyed on by larger crabs, snails, worms, and cephalopods. [13]

Deep Sea Reefs

The deep sea has coral reefs, too! There are actually three types of corals, depending on how deep they live:

-

Live in waters less than 98 ft deep (30 m)

Adapted to live in warm, sunlit waters

Can only be found in tropical waters

Have photosynthetic symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) and depend on them to produce food, but also catch some food with tentacles

Come in a range of shapes, including dense boulder-shaped colonies

[19]

-

Where these reefs live depends on how clear the water is and how deep light can penetrate!

Some mesophotic reefs are 98-164 ft deep (30-50m [19]), while others in clear, tropical waters are 98-490 ft deep (30-150 m) [20]

Adapted to live in cooler, lower-lit waters [19]

Can be found in tropical and subtropical waters [20]

Have zooxanthellae and get some food from them, and also catch food with tentacles [19]

Usually grow in shapes that maximize light absorption [19]

-

Depending on how deep light can penetrate, some deep-sea corals are found deeper than 164 ft [19], and others are found deeper than 490 ft (150+ m) [20]

Adapted to live in cold waters 39-54˚F down to 30˚F with little to no sunlight [19]

Can be found in waters anywhere in the world [21]

Do not have zooxanthellae and only catch food with tentacles [19]

They usually grow in shapes that maximize surface area in which to catch food particles drifting through the water, like fan, feather, and tree shapes. [21]

Check out this video of some incredible mesophotic reefs in the Marianas.

Video from the E/V Nautilus’ 2025 Mattingan: Mariana Arc Volcanic Exploration (NA171) expedition, by the Ocean Exploration Trust/ Nautilus Live, NOAA

In addition to the abundant shallow-water coral reefs surrounding the Mariana Islands, our region is also home to expansive deep-sea coral ecosystems. To date, over 100 species of deep-sea corals (50+ m deep) have been documented in the Mariana Trench and Mariana Arc of Fire National Wildlife Refuges within the Mariana Trench Marine National Monument. [22]

Deep-sea corals and sponges make a great habitat for deep-sea fish, crabs, brittle stars, worms, and other organisms. These organisms often are wrapped around or hanging onto coral branches while feeding in the current, or hiding inside their delicate and complex structures. Deep-sea corals make such a great habitat for other species that they are bustling with life and are considered hotspots for biodiversity in the deep sea! [23]

Vertical Migration

Did you know that the biggest animal migration in the world has been happening every single day in the deep sea? It’s true! This is called the vertical migration.

Many creatures move between the deep and surface waters on a daily basis! They swim downwards during the day to hide from predators in the darkness of the deep, and then swim hundreds or thousands of feet up towards the surface to hunt for food at night. Every day, thousands of species complete this vertical migration (also known as diel vertical migration, or diurnal vertical migration).

This daily vertical migration connects the deep sea to other ocean ecosystems.

-

Daily vertical migration plays a very important role in the carbon cycle: when deep-sea species eat shallow-water species and then return to the depths, their poop, which is full of carbon, sinks to the bottom of the ocean. This carbon stays in the deep sea instead of breaking down near the surface and releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. [24]

This mass migration can be so large that it can create a sort of turbulent whirlpool effect. This water movement can stir up nutrients and particles, distributing them to parts of the ocean where they wouldn’t otherwise be found. [24]

For the longest time, humans had no clue that daily vertical migration was happening! In fact, during World War II, the U.S. Navy was looking for enemy submarines using sonar, and instead of finding these submarines, the sonar picked up something strange: the seafloor appeared to be changing depth, getting shallower at night and deeper during the day.

What they thought was the seafloor changing depth ended up being a mass of plankton, fish, and other deep-sea creatures that were migrating to shallow waters each night to find food, and then returning to the deep sea before daybreak. The mass of creatures doing this was so dense that it reflected the sound waves of the sonar equipment! Scientists can still use sonar to detect and study the “layer of creatures” that migrate between deep and shallow waters. [25]

Our Connections to the Deep

While the deep sea may seem far away and “out of sight, out of mind”, we are more connected to it than one might think.

Benefits provided by deep-sea ecosystems

-

The deep sea is home to thousands of species, all of which play a crucial role in the balance of the ecosystem.

We know very little about deep-sea creatures, so there is enormous potential for discovering new species in the deep sea.

Tuna, swordfish, whales, sharks, and other large shallow-water species are known to dive into the deep sea to hunt for prey. These species, some of which are commercially important, rely on a healthy deep-sea ecosystem for their source of food. [25]

In Guam, deep-sea bottom fishing is a popular fishing technique for catching deep-sea fish by dropping a baited hook and line 491-984 ft (150-300 m) down into the water. [26] These deep-sea fish, like jacks, snappers, and groupers, are an important food source for many local residents.

Globally, deep-sea fisheries were estimated to have an economic value of $9.5 billion/year in 2014. [27]

Pictured here is a long-tail red snapper, or Onaga (Etelis coruscans), spotted in the Mariana Trench near the island of Pagan, CNMI. Onaga, also known as Abuninas in CHamoru, are often caught using bottomfishing techniques.

Photo: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas

-

Scientists have discovered chemicals in deep-sea species that can be used in modern medicine. With as little as we know about the deep sea, there is a huge potential for more medical discoveries.

For example, the main chemical in the cancer treatment drug Halaven was derived from deep-sea sponges. [27]

-

The deep sea is known as a “carbon sink”, meaning that it absorbs more carbon dioxide than it releases. In fact, it is considered the largest carbon sink on Earth. [28] Just like trees fight climate change, phytoplankton (tiny plant-like plankton in the ocean) also "breathe" in carbon dioxide and store that carbon in their bodies." The ocean contains immense amounts of plankton, and when they die, some of their bodies sink to the bottom of the ocean. Zooplankton that eat phytoplankton may also poop little pellets that sink into the deep. The carbon-rich phytoplankton remains, and zooplankton poop stays locked away in the deep-sea sediments that accumulate over thousands of years. The deep sea’s ability to store carbon prevents more carbon dioxide from accumulating in our atmosphere, which is the primary contributor to climate change.

The value of carbon stored in the deep sea is valued at 159 billion USD per year. [27]

Threats to deep-sea ecosystems

Overharvesting deep-sea species

Due to the extremely cold temperatures in the deep ocean, many deep-sea species tend to be slow-growing, long-lived, and extremely slow to reproduce. Overfishing or overharvesting deep-sea species can quickly decimate populations, leading to a major shift in the balance of predator and prey relationships.

-

Some deep-sea corals, such as red or pink coral (family Coralliidae), gold corals (Gerardia spp.), bamboo corals (Acanella and Lepidisis spp.), and black corals (order Antipatharia), are highly sought after in the jewelry trade. These corals have historically been overharvested, causing significant damage to deep-sea reef ecosystems. [27]

Two species of black corals, one species of bamboo coral, 2 species of red/pink corals, and 1 species of gold coral have been found in Guam’s deep-sea reefs [22]

Many deep-sea corals are incredibly long-lived. In fact, one species of deep-sea gold coral (Gerardia spp.) can grow up to 2,700 years! [29]

Pictured here is the precious red coral (Corallium sp.) found in the Mariana Trench in a 2016 expedition.

Photo: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas

In other parts of the world, deep-sea sharks like the gulper shark are overharvested for their squalene, which is a kind of oil found in the shark’s liver that is highly sought after in cosmetics.

These sharks take a very long time to mature and have very few pups, so overfishing them means it will take decades for their populations to bounce back. In some areas, gulper shark populations have declined by more than 80%. [30] On top of this, there are very few regulations protecting these deep-sea sharks.

Dumping and land-based litter

Even though the deep-sea may be very far away from the coastal communities where we live, the trash we generate on land can still make its way into the depths of the ocean.

-

For example, in a 2016 expedition exploring the Mariana Trench, they discovered an empty can of Spam (pictured here) resting on the seafloor 16,230 ft deep (4,947 m). Nearby, they also discovered a can of Budweiser and several plastic bags. [31]

On another expedition, scientists found that deep-sea crabs living in parts of the Mariana Trench were contaminated with 50 times more toxic chemicals than crabs found in heavily polluted rivers in China. [31]

The deep-sea has also been used as a dumping ground for chemicals and waste on multiple occasions.

For example, in the early 2010s, scientists discovered 25,000 barrels of the pesticide DDT that were dumped into the deep-sea near Los Angeles, California. [32] DDT was banned in the 1970s due to its harmful effects on wildlife, and these barrels dumped on the seafloor have been leaking this toxic chemical ever since then, affecting deep-sea species and ecosystems.

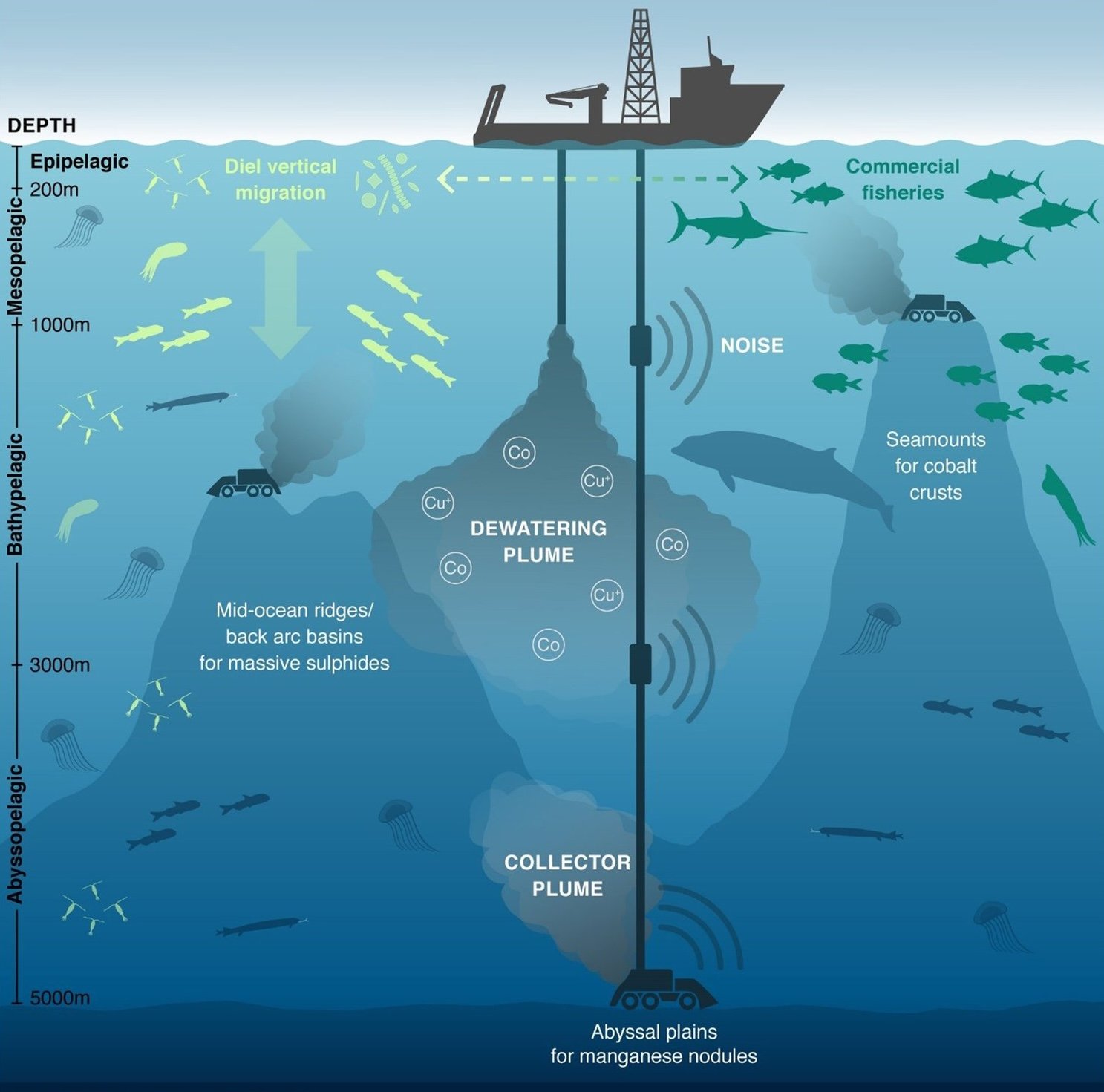

Extractive deep-sea mining

In some areas, the deep seafloor is rich with minerals like cobalt, nickel, aluminum, and manganese, which are highly sought after for manufacturing batteries and other electronics. However, deep-sea mining practices are invasive and leave a trail of destruction in deep-sea ecosystems.

-

Sediment plumes

During the process of mining minerals in the deep seafloor, large amounts of sediment get stirred up on the seafloor where the mining occurs, creating a sediment plume. The mined minerals get pumped up onto the ship, and the wastewater full of excess sediment gets pumped back into the ocean, creating another sediment plume.

Pictured here is a diagram of this process. Graphic by Amanda Dillon.

These sediment plumes are like underwater sandstorms and don’t just affect the immediate area. In fact, studies have shown that sediment plumes can spread tens or hundreds of miles beyond the mining site and can wreak havoc on ocean ecosystems. [33]

Sediment plumes harm marine life in many ways. These clouds of sediment in the open ocean can poison species that accidentally mistake the particles for food, disrupt the migration of commercially important species like tuna, clog fish’s gills, and increase stress hormones. [34]

For example, a 2020 study of a mining test off the coast of Japan found that there was a 43% decrease in the number of fish and shrimp in areas impacted by the sediment plume for up to a year after the mining took place. [35]

When the seafloor is disturbed, it takes decades to recover, if at all

Deep-sea mining involves removing chunks of the seafloor, including all of the corals, sponges, anemones, and other reef-building species that were anchored onto this part of the seabed. When this is destroyed, all the small crabs, fish, shrimp, and other species that found shelter in these reef-building species will also be destroyed or displaced.

Reef-building species in the deep sea grow incredibly slowly and cannot quickly re-populate areas that have been stripped bare. In many cases, they are unable to recover at all.

For example, a 2023 study found that a deep-seafloor area that underwent a mining experiment in 1979 had still not fully recovered 44 years later. Tracks left by the mining vehicles were also still visible on the seafloor as if they were still fresh. [36]

More than any of these, the biggest threat to the deep-sea is our lack of knowledge.

The decisions we make today jeopardize the current and future health of deep-sea ecosystems and may cause irreversible damage, yet decisions are made without knowing the extent of these impacts.

-

We have only observed 0.0006-0.001% of the deep seafloor since 1958. [37]

What can we do to protect the deep?

A small octopus spotted in the Mariana Trench. Photo: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

-

Within the Mariana Trench National Monument, commercial fishing is prohibited in the Islands Unit, though it is allowed in the Trench and Volcanic Units as long as other commercial fishing regulations are followed. Recreational fishing is allowed in the Monument if the fishing boat owner and operator have obtained a fishing permit. [38]

Within the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ), a federal permit is required to harvest deep-sea precious corals such as black, pink, red, gold, and bamboo corals. No permits have been issued for harvesting precious corals from Guam since 2007. [39]

-

There are several groups that regularly conduct deep-sea exploration and sometimes lead expeditions in the Marianas. Learn more about a few of these organizations or follow them on social media to stay updated:

The Nautilus Live | Ocean Exploration Trust @nautiluslive

NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration @noaaoceanexploration

Schmidt Ocean Institute @schmidtocean

-

Follow us on social media for updates @guamcoralreefs !

Here are several other groups to follow who may share content related to deep-sea issues in the Marianas:

Friends of the Mariana Trench @friendsofthemarianatrench

Pacific Islands Heritage Coalition @pihcoalition

The Ocean Discovery League @oceandiscleague

Prutehi Guahan @prutehi_gu

Future Swell @futureswell

-

Pink and red corals are deep-sea corals most frequently used in jewelry, and can be overharvested from deep-sea ecosystems.

To avoid potential deep-sea impacts, choose jewelry made from other materials.

-

Instead, look for products that are vegan or use plant-based squalene. This ensures that the products you buy aren’t coming at the expense of overfished deep-sea sharks.

-

Check out GCRI’s deep-sea resources

Consider applying for the Ocean Discovery League’s Accessing the Deep: Deep Ocean Training and Mentoring Program

Consider applying to sail aboard the Nautilus on one of their deep-sea exploration expeditions

Deep-Sea Inhabitants of the Marianas

Want to learn more?

Click here to check out deep-sea resources!

Want to teach about the deep sea in your classroom? Explore our library of deep-sea resources for teachers.

Background photos from the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas, unless otherwise specified

-

[1]https://www.oceandiscoveryleague.org/about

[2]https://www.nsf.gov/science-matters/dive-research-worlds-ocean

[3]https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-zones/sunlit-zone/

[5]https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-zones/midnight-zone/

[6]https://www.noaa.gov/jetstream/ocean/layers-of-ocean

[7]https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-zones/hadal-zone/

[8]https://www.britannica.com/place/Challenger-Deep

[9]https://www.fws.gov/national-monument/mariana-trench-marine

[10]https://deepseachallenge.com/the-expedition/the-mariana-trench/

[11]https://www.hawaii.edu/news/2021/04/06/ocean-deepest-point-grad-student/

[12]https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2024-06/appendix-1-mtmnm-mp-v.6.3.24.pdf

[13]https://deepseachallenge.com/the-science/marianas-trench-marine-national-monument/

[15]https://today.ucsd.edu/story/researchers_identify_mysterious_life_forms_in_the_extreme_deep_sea

[17]https://e3.eurekalert.org/news-releases/606889

[18]https://www.livescience.com/23387-mariana-trench.html

[19]https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/edu/materials/deep-sea-corals-fact-sheet.pdf

[20]https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/mesophotic.html

[21]https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/habitat-conservation/deep-sea-coral-habitat

[23]https://coastalscience.noaa.gov/science-areas/coral-ecosystem/deep-sea-corals/

[24]https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/ocean-fact/vertical-migration/

[25]https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/how-the-ocean-works/ocean-zones/twilight-zone/

[26]https://www.uog.edu/_resources/files/ml/technical_reports/132Kerr_2011_UOGMTechRep132.pdf

[28]https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/climate/articles/10.3389/fclim.2023.1169665/full#F1

[29]https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/02/080214130404.htm

[30]https://www.ifaw.org/au/journal/deepwater-sharks-cosmetics-cites-decision-extinction

[33]https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2011914117

[34]https://www.nature.com/articles/s44183-023-00016-8

[35]https://nyadagbladet.se/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/PIIS0960982223008151.pdf

[36]https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08921-3

[37]https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adp8602

[39]https://www.wpcouncil.org/fisheries/guam-mariana-archipelago/